CFTC Mission

To foster open, transparent, competitive, and financially sound markets to avoid systemic risk; and to protect market users and their funds, consumers, and the public from fraud, manipulation, abusive practices related to derivatives and other products that are subject to the Commodity Exchange Act.

A Message from

the Chairman

I am pleased to present the Fiscal Year (FY) 2016 Agency Financial Report for the U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC or Commission). The pages that follow will detail the agency’s performance, accomplishments, and audited financial statements for this period.

How This Report

is Organized

The Reports Consolidation Act of 2000 authorizes Federal agencies, with OMB concurrence, to consolidate various reports in order to provide performance, financial, and related information in a more meaningful and useful format. The Commission has chosen an alternative to the consolidated Performance and Accountability Report and instead, produces an Agency Financial Report (AFR), Annual Performance Report, and a Summary of Performance and Financial Information, pursuant to OMB Circular A-136, Financial Reporting Requirements.

Management's Discussion

and Analysis

The Management’s Discussion and Analysis section is an overview of the entire report. This section presents performance and financial highlights for FY 2016 and discusses compliance with legal and regulatory requirements, and evolving business trend and events.

-

-

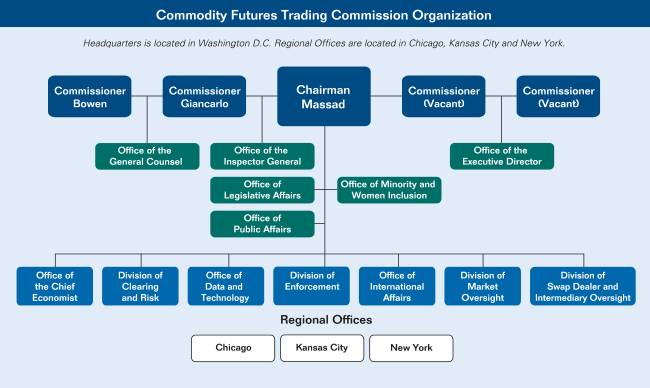

Organization and Location

The Commission consists of five Commissioners, with two positions currently vacant. The President appoints and the Senate confirms the CFTC Commissioners to serve staggered five-year terms. No more than three sitting Commissioners may be from the same political party. With the advice and consent of the Senate, the President designates one of the Commissioners to serve as Chairman.

The Office of the Chairman oversees the Commission’s principal divisions and offices that administer and enforce the Commodity Exchange Act (CEA) and the regulations, policies, and guidance thereunder.

The Commission is organized largely along programmatic and functional lines. The four programmatic divisions—the Division of Clearing and Risk (DCR), Division of Enforcement (DOE), Division of Market Oversight (DMO), and the Division of Swap Dealer and Intermediary Oversight (DSIO)—are partnered with, and supported by, a number of offices, including the Office of the Chief Economist (OCE), Office of Data and Technology (ODT), Office of the Executive Director (OED), Office of the General Counsel (OGC), and the Office of International Affairs (OIA). The Office of the Inspector General (OIG) is an independent office of the Commission.

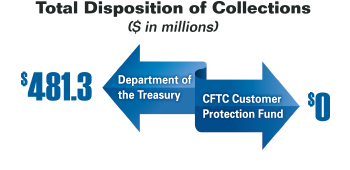

The Dodd-Frank Act established the CFTC Customer Protection Fund for the payment of awards to whistleblowers, through the whistleblower program, and the funding of customer education initiatives designed to help customers protect themselves against fraud or other violations of the CEA or the rules or regulations thereunder.

The Commission is headquartered in Washington D.C. Regional offices are located in Chicago, Kansas City and New York. The CFTC organization chart is also located on the Commission’s website at http://www.cftc.gov/About/CFTCOrganization/index.htm.

-

The CFTC Organization

Below are brief descriptions of the organizations:

The Commission

The Offices of the Chairman and the Commissioners provide executive direction and leadership to the Commission—specifically, as it develops and adopts agency policy that implements and enforces the CEA and amendments to the Act, and the Dodd-Frank Act. Commission policy is designed to foster the financial integrity and economic utility of derivatives markets for hedging and price discovery, to conduct market and financial surveillance, and to protect the public and market participants against manipulation, fraud, and other abuses.

Office of the General Counsel

The OGC provides legal services and support to the Commission and all of its programs. These services include: 1) engaging in defensive, appellate, and amicus curiae litigation; 2) assisting the Commission in the performance of its adjudicatory functions; 3) providing legal advice and support for Commission programs; 4) assisting other program areas in preparing and drafting Commission regulations; 5) interpreting the CEA; 6) overseeing the Commission’s ethics program and compliance with laws of general applicability; and 7) providing advice on legislative and regulatory issues.

Office of the Inspector General

The OIG is an independent organizational unit at the CFTC. The mission of the OIG is to detect waste, fraud, and abuse and to promote integrity, economy, efficiency, and effectiveness in the CFTC’s programs and operations. As such it has the ability to review all of the Commission’s programs, activities, and records. In accordance with the Inspector General Act of 1978, as amended, the OIG issues semiannual reports detailing its activities, findings, and recommendations.

Office of the Executive Director

The OED, by delegation of the Chairman, directs the internal management of the Commission, ensuring the Commission’s continued success, continuity of operations, and adaptation to the ever-changing markets it is charged with regulating; directing the effective and efficient allocation of CFTC resources; developing and implementing management and administrative policy; and ensuring program performance is measured and tracked Commission-wide. The OED includes the following programs: Business Management and Planning, Executive Secretariat (which includes Counsel to the Executive Director, Library, Records, and Privacy, and Proceedings), Financial Management, Human Resources, and Customer Outreach. The Office of Proceedings has a dual function to provide a cost-effective, impartial, and expeditious forum for handling customer complaints against persons or firms registered under the CEA, and to administer enforcement actions, including statutory disqualifications, and wage garnishment cases. The Office of Customer Education and Outreach administers the Commission’s consumer anti-fraud and public education initiatives.

Office of the Chief Economist

The OCE provides economic analysis, advice and context to the Commission and to the public. The OCE provides perspectives on both current topic and long-term trends in derivatives markets. The extensive research and analytical backgrounds of staff ensure that analyses reflect the forefront of economic knowledge and econometric techniques. The OCE plays an integral role in the cost-benefit considerations of Commission regulations and collaborates with staff in other divisions to ensure that Commission rules are economically sound. The OCE and the research it provides also play a key role in transparency initiatives of the Commission.

Division of Clearing and Risk

The DCR oversees derivatives clearing organizations (DCOs) and other market participants that may pose risk to the clearing process including futures commission merchants, swap dealers, major swap participants, and large traders, and the clearing of futures, options on futures, and swaps by DCOs. The DCR staff: 1) prepare proposed regulations, orders, guidelines, and other regulatory work products on issues pertaining to DCOs; 2) review DCO applications and rule submissions and make recommendations to the Commission; 3) make recommendations to the Commission of which swaps should be required to be cleared; 4) make recommendations to the Commission as to the eligibility of a DCO seeking to clear swaps that it has not previously cleared; 5) assess compliance by DCOs with the CEA and Commission regulations, including examining systemically important DCOs at least once a year; and 6) conduct risk assessment and financial surveillance through the use of risk assessment tools, including automated systems to gather and analyze financial information, and to identify, quantify, and monitor the risks posed by DCOs, clearing members, and market participants and its financial impact.

Office of Data and Technology

The ODT is led by the Chief Information Officer and delivers services to CFTC through four components: Systems and Services, Data Management, Infrastructure and Operations, and Policy and Planning. Systems and Services focuses on several areas: 1) market and financial oversight and surveillance; 2) enforcement and legal support; 3) document, records, and knowledge management; 4) CFTC-wide enterprise services; and 5) management and administration. Systems and Services provide access to data and information, platforms for data analysis, and enterprise-focused automation services. Data Management focuses on data analysis activities that support data acquisition, utilization, management, reuse, transparency reporting, and data operations support. Data Management provides a standards-based, flexible data architecture; guidance to the industry on data reporting and recordkeeping; reference data that is correct; and market data that can be efficiently aggregated and correlated by staff. Infrastructure and Operations organizes delivery of services around network infrastructure and operations, telecommunications, and desktop and customer services. Delivered services are highly available, flexible, reliable, and scalable, supporting the systems and platforms that empower staff to fulfill the CFTC mission. Policy and Planning focuses on information technology (IT) security, strategic and operational planning, IT policy and procedure development, configuration management, enterprise architecture, and internal business management. The four service delivery components are unified by an enterprise-wide approach that is driven by the Commission’s strategic goals and objectives.

Division of Enforcement

The DOE investigates and prosecutes alleged violations of the CEA and Commission regulations. The Commission’s enforcement efforts are necessary for public confidence and trust in the financial markets. DOE utilizes its authority to, among other things: 1) shut down fraudulent schemes and seek to immediately preserve customer assets through asset freezes and receivership orders; 2) uncover and stop manipulative and disruptive trading; 3) ensure that markets, firms, and participants subject to the Commission’s oversight meet their obligations, including their financial integrity and reporting obligations, as applicable; 4) ban certain defendants from trading in its markets and being registered; and 5) obtain orders requiring defendants to pay restitution, disgorgement, and civil monetary penalties. DOE also engages in cooperative enforcement work with domestic, state and Federal, and international regulatory and criminal authorities. The Whistleblower Office within DOE receives tips, complaints and referrals of potential violations, which allows the staff to bring cases more quickly and with fewer agency resources, and guides the handling of whistleblower matters as needed during investigation, litigation, and award claim processes.

Office of International Affairs

The OIA advises the Commission regarding international regulatory initiatives; provides guidance regarding international issues raised in Commission matters and in matters pertaining to cooperation arrangements with foreign authorities; represents the Commission in international fora, such as International Organization of Securities Commissions (IOSCO), the OTC Derivatives Regulators Group, and various Financial Stability Board committees; participates in bilateral dialogues, such as the U.S.-EU Joint Financial Regulatory Forum and the U.S.-China Strategic and Economic Dialogue; coordinates Commission policy as it relates to policies and initiatives of major foreign jurisdictions, the G20, Financial Stability Board and the Treasury; and provides technical assistance to foreign market authorities.

Division of Market Oversight

The DMO fosters markets that accurately reflect the forces of supply and demand for the underlying commodities and are free of disruptive activity. To achieve this goal, DMO oversees trading organizations, performs market surveillance, reviews new applications for exchanges, SEFs, and data repositories, and examines existing trading organizations and data repositories to ensure their compliance with the applicable core principles. Other important work includes evaluating new products to ensure the products are not susceptible to manipulation, and reviewing entity rules to ensure compliance with the CEA and CFTC regulations.

Division of Swap Dealer and Intermediary Oversight

The DSIO oversees the registration and compliance activities of market intermediaries and the futures and swaps industry self-regulatory organizations, which includes the National Futures Association (NFA). DSIO develops and implements regulations concerning registration, fitness, financial adequacy, sales practices, risk management, business conduct, capital and margin requirements, protection of customer funds, cross-border transactions, and anti-money laundering programs, as well as policies for coordination with foreign market authorities and emergency procedures to address market-related events. DSIO provides guidance to the Commission, intermediary registrants, self-regulatory organizations and other market participants regarding these regulations and the CEA provisions that these regulations implement. DSIO also monitors the compliance of these registrants and provides oversight and guidance for complying with the system of registration and compliance established by the CEA and the Commission’s regulations. DSIO further assesses registrant compliance with the CEA and CFTC regulations by conducting targeted reviews and examinations of registrants and performing oversight of the self-regulatory organization examination functions.

-

Our People

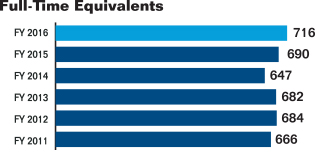

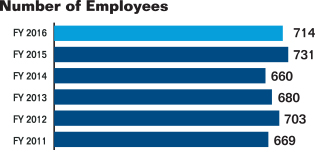

Collectively, the Commission employs 714 full-time permanent employees that compute to 716 full-time equivalents (FTE1) in FY 2016. CFTC staff are comprised of 74 percent direct mission staff (attorneys, economists, auditors, risk and trade analysts, and other financial specialists) and 26 percent management and support staff to accomplish four strategic goals and one management objective in the regulation of commodity futures, options, and swaps.

Attorneys across the CFTC’s divisions and offices represent the Commission in administrative and civil proceedings, assist U.S. Attorneys in criminal proceedings related to CEA violations, assist other domestic and international criminal and regulatory authorities, develop regulations and policies governing clearinghouses, exchanges and intermediaries, and monitor compliance with applicable rules.

Auditors, Investigators, Risk Analysts, and Trade Practice Analysts examine records and operations of derivatives exchanges, clearinghouses, and intermediaries for compliance with the provisions of the CEA and the Commission’s regulations.

Economists and Data Analysts monitor trading activities and price relationships in derivatives markets to detect and deter price manipulation and other potential market disruptions. Economists also analyze the economic effect of various Commission and industry actions and events, evaluate policy issues and advise the Commission accordingly.

Management Professionals support the CFTC mission by performing strategic planning, information technology, human resources, staffing, training, accounting, budgeting, contracting, procurement, and other management operations.

1 In the U.S. Federal Government, “FTE” is defined by the U.S. Government Accountability Office, as the number of total hours worked divided by the maximum number of compensable hours in a full-time schedule as defined by law. (back to text)

-

CFTC Regulatory Landscape – Part 1

CFTC Mission

To foster open, transparent, competitive, and financially sound markets to avoid

systemic risk; and to protect market users and their funds, consumers, and the

public from fraud, manipulation, and abusive practices related to derivatives

and other products that are subject to the Commodity Exchange Act.DERIVATIVE

is a financial instrument, traded on or off an exchange, the price of which is directly dependent upon (i.e., derived from) the value of one or more underlying securities, equity indices, debt instruments, commodities, other derivative instruments, or any agreed upon pricing index or arrangement (e.g., the movement over time of the Consumer Price Index or freight rates). Derivatives include futures, options, and swaps.

The Commission administers the CEA, 7 U.S.C. section 1, et seq. The 1974 Act brought under Federal regulation futures trading in all goods, articles, services, rights and interests; commodity options trading; leverage trading in gold and silver bullion and coins; and otherwise strengthened the regulation of the commodity futures trading industry. The Commission’s mandate has been renewed and expanded several times since then, most recently by the 2010 Dodd-Frank Act.

In carrying out this mission and to promote market integrity, the Commission polices the derivatives markets for various abuses and works to ensure the protection of customer funds. Further, the agency seeks to lower the risk of the futures and swaps markets to the economy and the public.

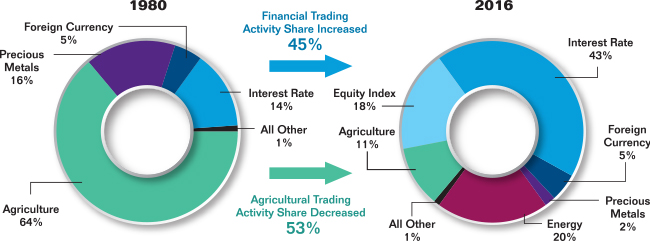

Derivatives first began trading in the United States before the Civil War, when grain merchants came together and created this new marketplace. When the Commission was founded in 1974, the majority of derivatives trading consisted of futures trading in agricultural sector products. These contracts gave farmers, ranchers, distributors, and end-users of products ranging from corn to cattle an efficient and effective set of tools to hedge against price risk.

The Commission construes the definition of a futures contract broadly. Essentially, it is an agreement to purchase or sell a commodity for delivery in the future: 1) at a price that is determined at initiation of the contract; 2) that obligates each party to the contract to fulfill the contract at the specified price; 3) that is used to assume or shift price risk; and 4) that may be satisfied by delivery or offset. The CEA generally requires futures contracts to be traded on regulated exchanges, with futures trades cleared and settled through clearinghouses, referred to as DCOs. To that end, futures contracts are standardized to facilitate exchange trading and clearing.

Although a futures contract agreement is set today, the person selling (for example, a farmer marketing bushels of wheat) will not receive payment and the buyer (in this case a bakery) will not receive goods purchased until the predetermined delivery date agreed to in the contract, which is November 1 in the following example. The farmer benefits from this agreement because he is certain as to the amount of money he will earn from the farming operation, even if the price of wheat changes between today and November 1. Similarly, the bakery buying the wheat also benefits by knowing how much the wheat will cost on November 1 and it will be better positioned to estimate its baking costs and set prices for its products. Finally, even though the actual price of wheat on November 1 (when the contract is fulfilled) may be greater or less than the pricing in the November 1 contract, the price is fixed and both the farmer and the bakery are bound by the price agreed to when they entered into the agreement. Most futures contracts are not settled with the actual physical delivery of the commodity, but by the purchase of opposite (offsetting) futures contracts, which serve to close out the original positions, with profits or losses dependent on the direction in which the price of the contracts have moved relative to those positions.

Speculators may also buy or sell such futures contracts. The speculator buying a futures contract for November wheat believes the value of the wheat in November will be higher than the price he is paying for the contract today. As time passes, and November draws closer, people may try to estimate whether the cost of November wheat will rise or fall, and may cause the value of that futures contract to fluctuate. For example, if people expect an especially bad harvest in November, then the price of November wheat will rise, and the speculator may sell that futures contract for November wheat for even more (or less) than he or she paid.

Over the years, the futures industry has become increasingly diversified. Futures based on other physicals, such as metals and energy products, were developed. Highly complex financial contracts based on interest rates, foreign currencies, Treasury bonds, security indexes, and other products have far outgrown the agricultural contracts in trading volume.

Source: Futures Industry Association.

Since 1980, the share of on-exchange commodity futures and option trading activity in the agricultural sector decreased from approximately two-thirds of trading activity to just over 10 percent of activity. The share of the financial futures and option contract activity increased from less than 20 percent of trading activity to approximately two-thirds of the trading activity. Among the other contracts, trading in energy contracts increased to approximately 20 percent of activity, from zero in 1980.

Electronic integration of cross-border markets and firms, as well as cross-border alliances, mergers and other business activities have transformed the futures markets and firms into a global industry. With the passage of the Dodd-Frank Act, the Commission was tasked with bringing regulatory reform to the swaps marketplace. Swaps, which had not previously been regulated in the United States, formed a collective global trading market valued in the hundreds of trillions of dollars when measured by notional amount.

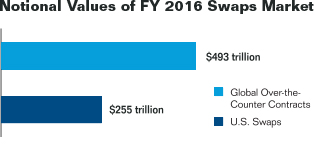

Sources: Bank of International Settlements, Global OTC Contracts. CFTC Weekly Swaps Report, U.S. Swaps.

The notional value of the U.S. swaps markets, as reported in the August, 2016 CFTC weekly swaps report, is commensurate to over 50 percent of the global OTC market. Data for the OTC contracts reflect global OTC data reported by the Bank of International Settlements, which compiles reports from 13 countries on different categories of OTC contracts. U.S. Swaps market data currently includes data from four swap data repositories (SDRs) and reflect data relating to interest rates and credit default swaps. The Commission expects to include additional SDRs and asset classes in the future.

Generally speaking, a swap is an exchange of one asset or liability for a similar asset or liability for the purpose of, inter alia, shifting risks, where the value of those payments is determined in the future based on some previously agreed measure. With a swap, counterparties agree to exchange future cash flows at regular intervals, with each cash flow calculated on a different (previously agreed-upon) basis. Before the Dodd-Frank Act, swaps were, for the most part, traded OTC (also called bilaterally), which means that swaps were not traded on regulated derivatives exchanges and many were not cleared through DCOs. Swaps are tools for hedging risks associated with, among other things, interest rates, currency fluctuations, and the cost of energy products, such as oil and natural gas. The value of a swap is derived from the value of the underlying asset or rate that serves as the basis for each (or both) legs of the exchange.

For example, two people may agree to swap the cost of a fixed interest rate on a $100,000 mortgage for a variable interest rate on a $100,000 mortgage. Person A agrees to pay a fixed interest rate of five percent to Person B, every month for a year. In exchange, Person B agrees to pay Person A variable interest rate based on the prime rate (currently 3.25 percent) plus 1.75 percent. Because these two interest rates equal each other at the time the swap is agreed, neither person owes anything to the other. If, however, the prime rate rises, then Person B will owe more money to Person A. Thus, at the time the swap is agreed, Person A is assuming interest rates will rise, whereas Person B is hoping interest rates will fall.

In normal times, these markets create substantial, but largely unseen, benefits for American families. During the 2008 financial crisis, however, their effect was just the opposite. It was during the financial crisis that many Americans first heard the term “derivatives”. That was because OTC swaps accelerated and intensified the crisis. The government was then required to take actions that today still stagger the imagination: for example, largely because of excessive swap risk, the government committed $182 billion to prevent the collapse of a single company—AIG—because its failure at that time, in those circumstances, could have caused our economy to fall into another Great Depression.

It is hard for most Americans to fathom how this could have happened. While derivatives were just one of many factors that caused or contributed to the crisis, the structure of some of these products created significant risk in an economic downturn. In addition, the extensive, bilateral transactions between the largest banks and other institutions meant that trouble at one institution could cascade quickly through the financial system. The opaque nature of this market meant that regulators did not know the level of exposure that any one institution or the financial system faced.

Registered Professionals

as of September 30, 2016Type of Registered Professional Number Associated Persons (AP) (Sales People) 53,431 Commodity Pool Operators (CPOs) 1,710 Commodity Trading Advisors (CTAs) 2,298 Floor Brokers (FBs) 3,816 Floor Traders (FTs) 694 Futures Commission Merchants (FCMs)2 68 Introducing Brokers (IBs) 1,275 Major Swap Participant (MSP) 0 Retail Foreign Exchange Dealer (RFEDs) 3 Swap Dealer (SDs) 102 TOTAL 63,397 Source: National Futures Association

Companies and individuals who handle customer funds, solicit or accept orders, or give trained advice must apply for CFTC registration through the National Futures Association, a self-regulatory organization with delegated oversight authority from the Commission. The Commission regulates the activities of over 63,000 registrants.2 Includes futures commission merchants that are also registered as retail foreign exchange dealers. (back to text)

-

CFTC Regulatory Landscape – Part 2

Dodd-Frank Act: Enhanced Regulatory Environment

On July 21, 2010, the Dodd-Frank Act was enacted and the CEA was significantly amended to establish a comprehensive new regulatory framework to include swaps, as well as enhanced authority over historically regulated entities.

The purpose of the derivatives provisions of the Dodd-Frank Act was to implement the commitments made by the United States at the G20 summit in Pittsburgh in 2009. The members of the G20 made four commitments:

- Require regulatory oversight of the major market players;

- Require clearing of standardized transactions through regulated DCOs;

- Require more transparent trading of standardized transactions; and

- Require regular data reporting so that regulators and market participants would have an accurate picture of what is going on in the market.

Regulatory Oversight

Six years ago, swap dealers faced no specific oversight with regard to their swap dealing activity. The first of the major directives Congress gave to the CFTC was to create a framework for the registration and regulation of swap dealers and major swap participants. The Commission completed this requirement. As of September 30, 2016, 102 swap dealers are provisionally registered with the CFTC.

The Commission has continued to adopt rules requiring strong risk management. In FY 2016, the CFTC strengthened the Dodd-Frank framework by releasing final rules for initial and variation margin requirements for uncleared swaps. These rules setting collateral requirements serve as the first line of defense in the event of a default, and are critically important to minimizing risk that can come from OTC swaps. There will always be a large part of the swaps market that is not cleared, as many are not suitable for central clearing because of limited liquidity or other characteristics. Moreover, DCOs will be stronger if greater care is exercised in what is required to be cleared. These rules protect against such activity posing excessive risk to the system.

The margin rules supplement the CFTC’s existing framework for OTC derivatives. This framework requires registered swap dealers and major swap participants to comply with various business conduct requirements, which include strong standards for documentation and confirmation of transactions, as well as dispute resolution processes. The regulations also include requirements to reduce risk of multiple transactions through what is known as portfolio reconciliation and portfolio compression. Further, they ensure that all counterparties are eligible to enter into swaps, and make appropriate disclosures to those counterparties of risks and conflicts of interest.

A dedicated swaps examination program is taking shape as well. Over the past two years, the CFTC has delegated additional responsibilities to and enhanced coordination efforts with the NFA, an industry funded, self-regulatory organization, to design and implement a direct examination process for swap dealers. By virtue of this, the Commission is now leveraging the significant resources of the NFA to meet cyclical exam workload demands for swap dealer registrants while preserving and focusing finite CFTC resources on NFA oversight, strategic horizontal and direct reviews, industry monitoring/surveillance and, when necessary, critical incident response.

As directed by Congress, the Commission has worked with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), other U.S. regulators, and our international counterparts to establish this framework. The Commission will continue this coordination to achieve as much regulatory consistency as possible in ways that best meet mutual goals and objectives.

Clearing

A second directive of the Dodd-Frank Act requires clearing of swaps that the Commission has determined under a five-part statutory framework should be cleared at DCOs. DCOs reduce the risk that one market participant’s failure could adversely impact other market participants or the public. DCOs accomplish this by standing in between the two original counterparties to a transaction—as the buyer to every seller and the seller to every buyer—and maintaining financial resources to cover potential defaults. DCOs value positions daily and require parties to post adequate margin on a regular basis. “Margin” is the collateral that holders of financial instruments have to deposit with DCOs to cover some or all of the risk of their positions. Collateral must be in the form of cash or highly liquid securities.

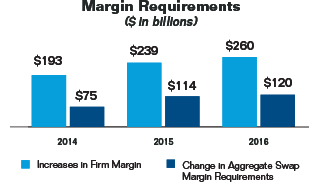

Source: Part 39 Data Filings Provided by DCOs.

In the past year, total margin requirements have increased $45 billion, or 17 percent. Futures account for about 57 percent of total margins, interest rate swaps about 33 percent and credit default swaps about 10 percent. Changes in total margin requirements can be due to changes in the size of cleared positions, or changes in volatility and margin rates.

The use of DCOs in financial markets is commonplace and has existed for over 100 years. The idea is simple: if many participants trade standardized products on a regular basis, the tangled, hidden web created by thousands of private two-way trades can be replaced with a more transparent and orderly structure, like the spokes of a wheel, with the DCO at the center interacting with market participants. In addition to facilitating trades, DCOs are required to monitor the overall risk and positions of each participant.

The CFTC was the first of the G-20 nations’ regulators to implement a regime for mandatory clearing of swaps. In 2013, the Commission required clearing for certain types of interest rate swaps denominated in U.S. dollars, Euros, Pounds and Yen, as well as credit default swaps on certain North American and European indices. In FY 2016, the CFTC expanded the interest rate swap clearing requirement to include those denominated in the Australian dollar, Canadian dollar, Hong Kong dollar, Singapore dollar, Mexican peso, Norwegian krone, Polish zloty, Swedish krona, and Swiss franc. These currencies have, or are expected soon, to mandate central clearing for these products, and these requirements will be phased-in based on when the corresponding clearing requirements have taken effect in non-U.S. jurisdictions.

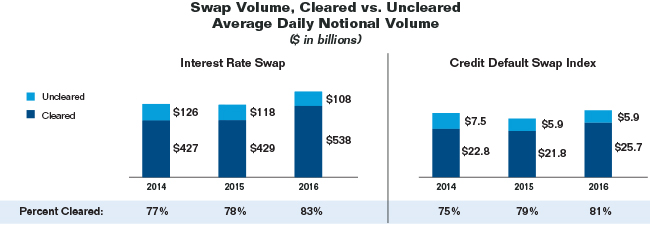

Based on data reported to SDRs, as of June 2016, 83 percent of all new interest rate swap transactions were cleared, as measured by notional value. This is compared to estimates by the International Swaps and Derivatives Association (ISDA) that only 16 percent by notional value, of outstanding interest rate swaps were cleared in December 2007. With regard to index credit default swaps, most new transactions are being cleared—81 percent of notional value, as of June 2016.

Source: International Swap Dealers Association.

According to the International Swap Dealers Association, the data shows an increasing number of interest rate and credit default swap trades were cleared as of June 2016. Visit http://www.isda.org for more details on market trends.

The Dodd-Frank Act’s approach to encouraging the use of central clearing for swaps and the accompanying CFTC rules for clearing swaps were patterned after the successful regulatory framework used for many years in the futures market. The Commission requires that clearing occurs through CFTC-registered DCOs that meet certain standards—a comprehensive set of core principles and regulations that ensures each DCO is appropriately managing the risk of its members, and monitoring them for compliance with important rules. Non-U.S. DCOs can receive exemptions, when they are subject to comparable, comprehensive supervision and regulation by the appropriate government authorities in their respective home country.

Of course, central clearing by itself is not a panacea. DCOs do not eliminate the risks inherent in the swaps market. The Commission must therefore be vigilant. It must do all it can to ensure that DCOs have financial resources, vigorous risk management tools, systems that minimize operational risk, and all the necessary standards and safeguards consistent with the core principles to operate in a fair, transparent and efficient manner. DCOs must also have tools in place to address a wide range of situations that may arise if a clearing member defaults, and they must develop plans to deal with losses to the DCO in non-default situations. In addition, the Commission must make sure that DCO contingency planning to deal with operational events, such as cyber-attacks, is sufficient.

To that end, throughout FY 2016, the Commission was intently focused on the resiliency of DCOs, as well as planning for recovery and resolution. These remain high priorities for the CFTC, and there is significant work taking place domestically and internationally. Domestically, the CFTC’s examination and risk surveillance programs focus on DCO resiliency on an ongoing basis. Commission staff is applying regulatory or supervisory stress tests for the largest DCOs, which assess the impact of stressful market scenarios across multiple DCOs and clearing members on the same date. Staff is also working with the major clearinghouses to make sure they have well-developed recovery plans in place. And staff has been actively engaged in working with the FDIC on resolution planning.

In addition, the CFTC has played a leadership role with regulators from around the world on issues related to the resilience, recovery, and resolution of clearinghouses. During FY 2016, CFTC staff continued its work with international regulators on a four-part international work plan on these issues. Indeed, all aspects of this plan, some of which are being led by CFTC staff, have contributed to the important progress made to create an international regulatory framework to ensure the strength and stability of these institutions.

Transparent Trading

The third area for reform under Dodd-Frank requires more transparent trading of standardized derivatives products. In the Dodd-Frank Act, Congress provided that certain swaps must be traded on a SEF or an exchange that is registered as a designated contract market (DCM). The Dodd-Frank Act defined a SEF as “a trading system or platform in which multiple participants have the ability to execute or trade swaps by accepting bids and offers made by multiple participants.” The trading requirement was designed to facilitate a more open, transparent and competitive marketplace, benefiting, among others, commercial end-users seeking to lock in a price or hedge risk.

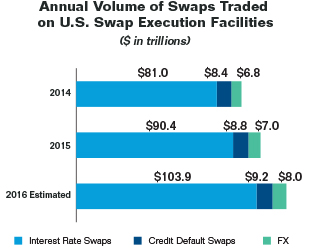

Source: Futures Industry Association.

In 2014, the Futures Industry Association began collecting volume data from SEFs, a new type of CFTC-regulated platform for trading swaps that began operating on October 2, 2013. The Futures Industry Association publishes data on volume and market share trends for interest rate, credit and foreign exchange (FX) products traded on SEFs. Visit SEF Tracker In-Depth at https://www.fia.org for more details on market trends.

The CFTC finalized its rules for SEFs in June 2013. Twenty-three SEFs have been registered with the CFTC, and one application is pending. These SEFs are diverse, but each is required to operate in accordance with the same core principles. These core principles provide a framework that includes obligations to establish and enforce rules, as well as policies and procedures that enable transparent and efficient trading. SEFs must make trading information publicly available, put into place system safeguards, and maintain financial, operational and managerial resources to discharge their responsibilities.

Trading on SEFs began in October 2013. As of February 2014, specified interest rate swaps and credit default swaps were required to be traded on a SEF or other regulated exchange. For the 2016 year-to-date, as of August 26, 2016, 56 percent of trading by notional volume in rates and credit was executed on SEFs. During this same period, notional value executed on SEFs generally has been in excess of $8 trillion monthly. It is important to remember that trading of swaps on SEFs is still new. SEFs are still developing best practices under the new regulatory regime. The new technologies that SEF trading requires are likewise being refined. Additionally, other jurisdictions have not yet implemented trading mandates, which has slowed the development of cross-border platforms. There will be issues as SEF trading continues to mature. The Commission will need to work through these to fully achieve the goals of efficiency and transparency SEFs are meant to provide.

Data Reporting

The fourth G20 reform commitment implemented by the Dodd-Frank Act was to require ongoing reporting of swap activity. Having rules that require oversight, clearing, and transparent trading is not enough. The Commission must have an accurate, ongoing picture of what is going on in the marketplace to achieve greater transparency and to address potential systemic risk. Title VII of the Dodd-Frank Act assigns the responsibility for collecting and maintaining swap data to swap data repositories (SDRs), a new type of entity necessitated by these reforms. All swaps, whether cleared or uncleared, must be reported to SDRs. There are currently four SDRs that are provisionally registered with the CFTC.

The collection and public dissemination of swap data by SDRs helps regulators and the public. It provides regulators with information that can facilitate informed oversight and surveillance of the market and implementation of our statutory responsibilities. Dissemination, especially in real-time, also provides the public with information that can contribute to price discovery and market efficiency. While the Commission has accomplished a great deal in this area, much work remains. The task of collecting and analyzing data concerning this marketplace requires intensely collaborative and technical work by industry and the agency’s staff. Going forward, it must continue to be one of the CFTC’s chief priorities.

There are three general areas of activity, and the Commission has made progress in all of them. First, the CFTC is making sure its data reporting rules and standards are specific and clear, and harmonized as much as possible across jurisdictions. In FY 2016, the Commission adopted a rule to create a simple, consistent process for reporting cleared swaps. The rule streamlines the reporting so there are not duplicate records of a swap, which can lead to double counting that can distort the data. It makes sure that accurate valuations of swaps are provided on an ongoing basis. And it eliminates a number of needless reporting requirements for swap dealers and major swap participants.

CFTC staff has also made progress in standardizing reporting to SDRs. During the fiscal year, staff published draft technical specifications for the reporting of 120 priority data elements. These describe the form, manner and the allowable values that each data element can have. The CFTC also is leading the international effort in this area, both in the global harmonization of data standards and in building internationally accepted governance structures to maintain those data standards. The Commission will abstain from finalizing domestic standards until this international work is complete, to ensure harmonization—and to achieve consistency in reporting across-borders.

The Commission must also make sure the SDRs collect, maintain, and publicly disseminate data in the manner that supports effective market oversight and transparency. The SDRs must have the ability to make sure the data they receive is complete and conforms to required standards.

Finally, market participants must live up to their reporting obligations. Ultimately, the market participants bear the responsibility to make sure that the data is accurate and reported promptly. The primary goal is to bring firms into compliance. But where firms fail repeatedly to take these obligations seriously or invest sufficient resources to meet them, the Commission has taken, and will continue to take, enforcement action.

-

Organization and Location

The Commission consists of five Commissioners, with two positions currently vacant. The President appoints and the Senate confirms the CFTC Commissioners to serve staggered five-year terms. No more than three sitting Commissioners may be from the same political party. With the advice and consent of the Senate, the President designates one of the Commissioners to serve as Chairman.

The Office of the Chairman oversees the Commission’s principal divisions and offices that administer and enforce the Commodity Exchange Act (CEA) and the regulations, policies, and guidance thereunder.

The Commission is organized largely along programmatic and functional lines. The four programmatic divisions—the Division of Clearing and Risk (DCR), Division of Enforcement (DOE), Division of Market Oversight (DMO), and the Division of Swap Dealer and Intermediary Oversight (DSIO)—are partnered with, and supported by, a number of offices, including the Office of the Chief Economist (OCE), Office of Data and Technology (ODT), Office of the Executive Director (OED), Office of the General Counsel (OGC), and the Office of International Affairs (OIA). The Office of the Inspector General (OIG) is an independent office of the Commission.

The Dodd-Frank Act established the CFTC Customer Protection Fund for the payment of awards to whistleblowers, through the whistleblower program, and the funding of customer education initiatives designed to help customers protect themselves against fraud or other violations of the CEA or the rules or regulations thereunder.

The Commission is headquartered in Washington D.C. Regional offices are located in Chicago, Kansas City and New York. The CFTC organization chart is also located on the Commission’s website at http://www.cftc.gov/About/CFTCOrganization/index.htm.

-

-

-

Forward Looking – Future Business Trends and Events – Part 1

There are some core principles that motivate the Commission’s work in implementing the Dodd-Frank Act. The first is that the CFTC must never forget the cost of the financial crisis to American families, and it must do all it can to address the causes of that crisis in a responsible way. The second is that the United States has the best financial markets in the world. They are the strongest, most dynamic, most innovative, most competitive and transparent. They have been a significant engine of U.S. economic growth and prosperity. The Commission’s work should strengthen U.S. markets and enhance those qualities in a way that does not place unnecessary burdens on the dynamic and innovative capacity of the industry.

It has now been eight years since the global financial crisis, and the Commission has taken a number of steps to improve the safety and soundness of our financial system. However, the work of the Commission does not just involve looking to the causes of past crises. An equally important part of the CFTC’s work is looking ahead, to the new opportunities and challenges facing these markets.

The financial markets are evolving and innovating at the speed of light. Transformations in technology are playing a large role in those changes, and from them come new opportunities as well as challenges. In turn, market participants are altering their activities—and strategies—in response. As the industry continues to evolve, the CFTC must also take steps—to ensure our regulatory framework is able to respond to the challenges ahead.

This understanding is critical to the Commission’s ability to appropriately regulate the industry of today and tomorrow. What follows is a brief discussion of what the Commission expects in the years to come.

Instances of Cyber-Attack Warrant Increased Vigilance

There is heightened attention, both domestically and internationally, on cybersecurity and the risk of cyber-attacks. Indeed, this may be the most significant risk to financial stability we face today. The CFTC is very focused on this issue, especially with respect to the core infrastructure in the markets it regulates—the clearinghouses, exchanges, trading platforms and data repositories. The CFTC already conducts regular examinations of registered entities to monitor compliance with system safeguards core principles and CFTC regulations. And in FY 2016, the Commission finalized new rules to address the risk posed by cyber-attack or other technological failures. These rules require the private companies that operate the core market infrastructure to regularly evaluate cyber risks and test their cybersecurity and operational risk defenses. They add greater definition to the Commission’s existing efforts—by setting principles-based standards and requiring specific types of testing, all rooted in industry best practices.

Recent cyber-attacks both inside and outside of the financial sector make clear the need for continued vigilance on this front. Through its participation in the Financial and Banking Information Infrastructure Committee, CFTC coordinates and cooperates with other financial regulators, the intelligence community, and Federal law enforcement agencies to ensure that Commission oversight is informed by current cyber threat information and trends. And the CFTC also continues to increase its own cybersecurity protections over the data collected from market participants for surveillance and enforcement.

The Opportunities and Challenges Posed by the Increased Use of Automated Trading

The Commission is also focused on the increased use of automated trading, which has become the dominant form of trading in the derivative markets. In recent years, there has been a fundamental change in this regard—approximately 70 percent of trading in the futures market is now automated. While there are positives that come from this technology, there is also a greater likelihood of disruption and other operational problems. The CFTC is taking steps to address these challenges. In FY 2016, the Commission issued a proposal that seeks to minimize the risk of that disruption caused by automated trading. The proposal relies on a principles-based approach that codifies many industry best practices. It requires pre-trade risk controls, such as message throttles and maximum order size limits. It requires other measures such as “kill switches,” which facilitate emergency intervention in the case of a malfunctioning algorithm. But it does not prescribe the parameters or limits of such controls; it leaves those specifics to market participants.

Growth in Clearing Means Increased Focus on Clearinghouse Resilience and Additional Requirements for Uncleared Swaps

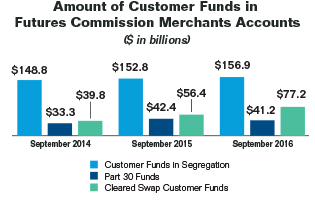

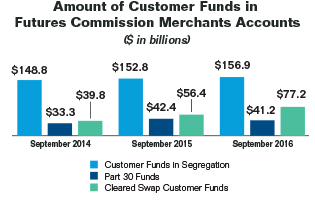

The segregation of customer funds from a futures commission merchant’s own proprietary funds for use is one of the core foundations of customer protection in the cleared swaps markets.Central clearing of standardized transactions, as required by Dodd-Frank, reduces credit risk between counterparties. Following the 2013 implementation of the Commission’s rules requiring that certain interest rate swaps and credit default swaps be cleared, a significant portion of the swaps market moved into central clearing. This shift in market behavior has significant risk mitigation benefits.

Source: CFTC Monthly Futures Commission Merchants Financial Reporting.

As a key component of the Commission’s regulatory framework, all customer funds held by an futures commission merchants for trading on DCMs (exchanges) and SEFs must be segregated from the futures commission merchant’s own funds—this includes cash deposits and any securities or other property deposited by such customers to margin or guarantees their futures and cleared swaps trading. In addition, Part 30 of the CFTC’s regulations also requires futures commission merchants to hold apart from their own funds a “secured amount” for customers trading futures contracts on foreign boards of trade through futures commission merchants.

Swap customers and other market participants are required to post initial margin to cover the potential future exposure of their positions in the event of default. In addition, swap customers and other market participants are required to pay variation margin through futures commission merchants to avoid the accumulation of large gain and/or loss obligations. In FY 2016, the CFTC adopted margin requirements for uncleared swaps entered into by swap dealers and major swap participants subject to the CFTC’s jurisdiction (i.e., non-bank swap dealers and major swap participants). The Commission also adopted a cross-border approach for the implementation of this rule—which helps protect against the possibility that risks created outside our borders will flow back into the United States. In addition to posting margin, the Commission is working to propose rules that will require non-bank swap dealers and major swap participants to hold minimum levels of capital. Completion of the rulemaking process is a top agency objective. Together, capital and margin requirements are intended to reduce swaps-related systemic risk in the global financial system and to encourage clearing. As DCOs offer new swaps for clearing, the CFTC will assess the ability of the DCO to properly manage the risk of clearing those swaps.

The movement of swaps to a cleared environment has mitigated systemic risk in the market but has also shifted significant new levels of counterparty risk to DCOs. As more swap activity migrates to clearing, DCOs are holding substantially more collateral that has been deposited by market participants. There is a need to perform examinations of DCOs to evaluate their resources and capabilities to monitor and control their financial and operational risks. There is a need for the CFTC to apply additional staffing resources to perform these large and complex examinations. And the CFTC is focused on doing so in the months and years ahead.

The Commission will continue its work on supervisory stress tests for the largest clearinghouses in our jurisdiction. These examinations assess the impact of stressful market scenarios across multiple DCOs and clearing members on the same date. The Commission will also continue to make sure the major DCOs have adequate recovery plans, and will continue its collaboration with the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation on resolution planning.

Further, the CFTC has taken a leadership role on an international work plan related to clearinghouse strength and stability. This ongoing work has four major elements, and staff are involved in all of them. First, the CFTC is co-chairing a working group looking at clearinghouse resilience and recovery issues, including whether the international regulatory standards, known as the Principles for Financial Market Infrastructures (PFMIs), have sufficient granularity. A second working group has assessed the implementation of the PFMIs at ten representative clearinghouses. Third, a separate group is working on resolution planning for clearinghouses, including international coordination. A final group is examining the interdependencies among global clearinghouses and major clearing members.

Resilient clearinghouses also depend on having a robust clearing member industry. There are many factors that affect the health of clearing members. This is a key focus for CFTC staff in the years ahead, and the Commission is already engaging with a wide array of market participants on this issue.

-

Forward Looking – Future Business Trends and Events – Part 2

Continuing to look at the Threshold for Registration as a Swap Dealer

The Commission recently acted to extend the phase-in of the de minimis threshold for swap dealing by one year. This threshold determines when an entity’s swap dealing activity requires registration with the CFTC. In 2012, the CFTC set the threshold initially at $8 billion in notional amount of swap dealing activity over the course of a year, and provided that it would fall to $3 billion at the end of 2017. This would have meant that firms would have been required to start determining whether their activity exceeds that lower threshold in January 2017.

The Commission took this step for several reasons. First, the delay provides more time to study the issue. CFTC staff recently completed a study required by the rule on the threshold. The study estimated that lowering the threshold would not increase significantly the percentage of interest rate swaps and credit default swaps covered by swap dealer regulation, but would require many additional firms to register, including some smaller banks whose swap activity is related to their commercial lending business. However, the study also notes that the data has certain shortcomings, particularly when it comes to nonfinancial commodity swaps, a market that is very different than the interest rate swaps and credit default swaps markets. The delay will allow the Commission to consider these issues further. In addition, the Commission has made clear its intention to adopt a rule setting capital requirements for swap dealers before addressing the threshold. This rule, required by Dodd Frank, is one of the most important in our regulation of swap dealers. The Commission will be looking closely at this issue, as well as the data that informs it, in the year ahead.

Clearing Firms and Customers Trade the Same Asset Class at Multiple DCOs

Firms and customers often clear the same asset classes at multiple DCOs. Each DCO’s view is limited to the position it clears, while the Commission has the unique perspective of being able to analyze positions and the risks that they pose across DCOs. The Commission has to ensure it has the data and tools necessary to evaluate the risk of these positions. The Commission should be able to ascertain if the positions at the multiple DCOs increase or offset risk. The Commission must further be able to determine if the firm or customer has the resources to cover the potential losses at each DCO and not require the gains at one DCO to pay the losses at the others.

Aggregating Cleared Swaps and Futures Risk

Many large swap accounts (firms and customers) also clear large futures positions. In many cases, the swaps and futures are cleared at the same firm. The Commission has to ensure it has the procedures in place to first identify these accounts. Secondly, the Commission has to ensure it has the software and information necessary to determine if the different asset classes increase or decrease risk. DCOs now and increasing in the future are offering cross-margin programs between asset classes. The Commission has to ensure it receives all position and account information for accounts in these programs. The Commission then has to have the software and expertise necessary to review and understand the risk and margin offsets present in the program.

New Regulatory Environment Driving Innovations in Derivatives Markets

The Commission will also continue to oversee the activities of existing SEFs and DCMs to ensure compliance with Commission regulations and the CEA. The industry is responding quickly to the competitive opportunities engendered by the shifting regulatory landscape—the introduction of futures contracts by DCMs that are economically equivalent to standardized swaps is one such example. Innovation in the industry, which is likely to increase in pace with the addition of SEFs, will continue to add complexity in ways currently unanticipated. For example, the Commission is seeing new methods for executing transactions that were not proposed in previous years. While these changes will impact all of the CFTC mission activities, the near-term impact will fall most heavily on the mission activities of registration, product review, examinations, enforcement, and economic analysis.

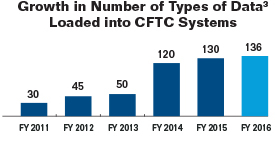

Exponential Growth in Data Must be Acquired, Validated, Warehoused, and Analyzed to Fulfill the Commission’s Regulatory Responsibilities

The Commission continues to enhance its software and automated tools to accommodate its enhanced surveillance responsibilities and access to data, including that generated by the swap data reporting rules, enhanced customer protection rules, other regulatory changes, increasing number of participants, and increasing number and complexity of data sources relevant to surveillance. The technology (data and processes) required for surveillance of swaps markets differs from that required for futures and options markets, and differs across asset classes. In addition, the ability to view risk across asset classes and in combination with futures is an overarching requirement that must also be automated and the Commission must continue to work closely with the SDRs, self-regulatory organizations and other Federal and international regulators (as appropriate) to harmonize how this data is recorded, organized, and stored. In response to the influx of new types of data from new and existing registrants, the CFTC must build its own information infrastructure and analytical capabilities to support its responsibilities as the primary regulator for the derivatives markets.

Source: Office of Data and Technology, CFTC.

The CFTC receives data from many new entities, such as clearing members, swap dealers, DCO’s, large banks and traders in futures and options markets, SDRs and SEFs, some of which did not provide data prior to the Dodd-Frank Act. The amount of data received and loaded onto CFTC systems over six years have more than quadrupled. CFTC currently has plans to receive automated data from up to 6,000 new reporting entities in the coming years. The 6,000 entities represent market participants that will be required to submit Form 404 reports electronically once the Ownership and Control Reporting (OCR) rule is fully implemented.

The CFTC is required to perform a comprehensive function that cannot be done by any single self-regulatory organization and needs to see data from all industry participants in the swaps and futures markets. In response to the influx of new types of data from new and existing registrants, the CFTC must continue to enhance and adjust its information infrastructure and analytical capabilities to support its responsibilities as a first line regulator. Only by providing advanced tools and enriched data for staff to connect, analyze, and aggregate data can the Commission apply its unique view of the derivatives market toward effective market and risk surveillance. With each additional set of data collected there are data, technology, and usage requirements:

- Defining data standards, such as financial information exchange markup language (FIXML) and financial products markup language (FpML), to collect data;

- Designing data repositories to facilitate data loading and integration;

- Developing software to load new data;

- Developing data validation mechanisms to report errors and metrics to submitters;

- Providing operations support to facilitate timely submission of data;

- Developing data profiles on data submissions, submitters, markets, etc. (not currently done); and

- Analyzing data in a wide variety of ways to support mission functions.

The Commission will continue to adapt its data architecture and data management practices to manage the exponential growth in the size and complexity of mission data and facilitate continuous improvements in data quality and the ability to isolate anomalous market activity and complex financial and systemic risk. It will also continue to bolster its own safeguards to protect this data from cyber-attack.

3 Swaps data include Part 20 and Part 39 interim records reporting files, additional by-rule development, Part 45 swaps data reporting, OCR-ownership and control reporting, and Volcker data. (back to text)

4 CFTC Form 40, Statement of Reporting Trader, is a reporting requirement for every person that holds a reportable position in accordance to Section 1804 of the CEA. The information requested is used generally in the Commission’s market surveillance activities to provide information concerning the size and composition of the commodity futures or option markets, and to permit the Commission to monitor and enforce the speculative position limits that have been established. The complete listing of routine uses, in accordance with the Privacy Act, 5 U.S.C. §522a, and the Commission’s rules thereunder, 17 Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) Part 146, of the information contained in these records is found in the Commission’s annual notice of its system of records. (back to text)

-

Forward Looking – Future Business Trends and Events – Part 3

Growth and Complexity of the Markets the Commission Oversees

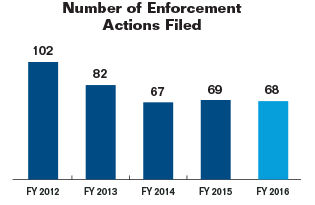

Enforcement remains critically important to maintain the integrity of our markets, deter bad behavior, and reinforce public confidence. The CFTC’s expanded mission coupled with the increased complexity of the markets and new, complicated forms of illegal behavior make the Commission’s enforcement responsibilities are more important than ever. The CFTC’s enforcement capabilities must keep pace with the challenges that go along with the growth and sophistication of financial markets and instruments. These include identifying and meeting the challenges arising from proliferation of sophisticated instruments trading in multiple venues and the increased prevalence of algorithmic and high-frequency trading. The Commission will also need to commit enforcement resources to understanding and investigating potential unlawful conduct within the Commission’s jurisdiction, including in evolving markets for derivatives and commodities, such as Bitcoin and other crypto-currencies or block chain technology. The Commission also foresees a continued increase in multi-jurisdictional and multi-national investigations given the global nature of the swaps marketplace and the challenges associated with substituted compliance. The Commission is also experiencing an increase in international enforcement investigations in its traditional markets. These cases are inherently more resource-intensive due to their cross-border nature and coordination with foreign authorities.

Specifically, the Commission is investigating more matters involving manipulation, false reporting of market information and disruptive trading practices, including spoofing. Often, these matters involve misconduct spanning many years and multiple markets and products, and require forensic economic analysis of trading data. In order to investigate and litigate market-wide violations, as well as those less complex but equally important retail fraud cases, the Commission has an increased need for specialized experts to work on enforcement cases. One example is the Commission’s work addressing fraud in the precious metals space, where we use our anti-fraud enforcement authority. Others include the Commission’s work prosecuting wrongdoers for fraudulent schemes like Ponzi schemes, deceptive practices related to commodity pools, and other efforts against those who try to perpetrate frauds against seniors and other retail investors.

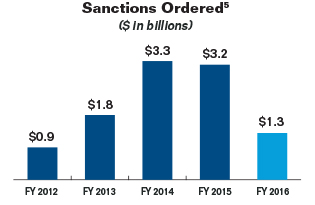

Source: Division of Enforcement, CFTC.

The CFTC utilizes every tool at its disposal to detect and deter illegitimate market forces. Through enforcement action, the Commission preserves market integrity and protects market participants.

Maintaining Integrity of Benchmarks

The integrity of benchmarks used in the derivatives market, such as the London Interbank Offered Rate (LIBOR), FX, and International Swaps and Derivatives Association Fix (ISDAFIX) remains a priority for the Commission. Over the last five years, the CFTC has imposed over $5.08 billion in penalties in 17 actions against banks and brokers to address ISDAFIX, FX, and LIBOR benchmark abuses to ensure the integrity of global financial benchmarks. Of this, over $1.8 billion in penalties has been imposed on 6 banks for misconduct relating to FX benchmarks, while over $3.21 billion has been imposed on 21 banks, as well as brokers, for misconduct relating to ISDAFIX, LIBOR, Euro Interbank Offered Rate (Euribor), and other interest rate benchmarks. These benchmarks are an essential valuation tool for thousands upon thousands of derivatives across financial markets, including: options on interest rate swaps, or swaptions; cross-currency swaps; foreign exchange swaps; spot transactions; forwards; options; and futures. These investigations require a significant allocation of enforcement resources due to the fact that they are global in nature and mandate intensive reconstruction of communications and trades requiring substantial documents, emails, and chat room reviews; analysis of trading data and books; outside experts; and reconstructing timelines.

In addition to the various enforcement actions, since 2013, as a member of the Official Sector Steering Group established by the Financial Stability Board, CFTC has been working with regulators and central banks from around the world to review standards and principles for sound benchmarks. This includes an assessment of the major interest rate benchmarks against the internationally agreed and endorsed IOSCO Principles for Financial Benchmarks. This effort included a report laying out plans for reform of major reference rates such as the LIBOR, Euribor, and the Tokyo Interbank Offered Rate.

A key component of the reform plans includes the development of alternative, nearly risk-free reference rates. CFTC staff has been working with the market participant-led Alternative Reference Rate Committee convened by the Federal Reserve to develop alternatives to the U.S. Dollar LIBOR as well as a transition strategy.

Protecting Customers from Fraud

Anti-fraud enforcement remains a core commitment of the CFTC’s enforcement program. During the past year, the Commission prosecuted wrongdoers for a wide range of fraudulent schemes, including Ponzi schemes that preyed upon the retail public’s hopes to participate in forex trading, precious metals speculation, and commodity pools. The Commission’s experience with fraudsters is that they gravitate towards, and flourish in, financial markets that are perceived to be subject to limited oversight. Therefore, the Commission must continue to devote significant resources to assure the integrity of the financial markets within its jurisdiction and to protect the retail public that wants to participate in them.

Ensuring that Markets, Firms and Participants Meet their Obligations

In protecting the markets and market participants, the Commission engages in investigations and takes enforcement action, when necessary, to make sure that firms maintain their financial integrity and that markets, firms and significant market participants fulfill their regulatory obligations. For example, the Commission conducts a comprehensive examination program to oversee compliance with the Dodd-Frank Act and Commission regulations. With the Dodd-Frank Act’s expansion of the Commission’s responsibility, CFTC staff is doing all it can with the available resources to ensure that the markets, firms and significant market participants uphold these essential obligations. The Commission also is making sure its registrants are meeting standards for their capitalization and handling of funds. These are intended to safeguard against market disruption and abuse from imprudent practices or intentional misconduct and to protect customers. Further, the Commission is focused on ensuring market participants are complying with reporting obligations. These requirements are essential to the CFTC’s ability to conduct effective surveillance of the futures and derivatives markets that it regulates.

Necessity for Continued Engagement with International Regulators

The 2008 financial crisis demonstrated how risks taken abroad by a large financial institution can result in, or contribute to, substantial losses to U.S. persons and threaten the financial stability of the entire U.S. financial system. These failures and near failures revealed the vulnerability of the U.S. financial system and economy to systemic risk resulting from among other things, poor risk management practices of certain financial firms, the lack of supervisory oversight for certain financial institutions as a whole, and the overall interconnectedness of the global swap business. Given the global nature of the swaps market, international cooperation among regulators has been, and will continue to be, essential to regulate effectively the financial markets.

This past year, the Commission worked closely with regulators across the globe on a number of fronts. For example, CFTC staff worked successfully to ensure rules setting margin for uncleared swaps were as similar as possible among major jurisdictions, including the U.S., Europe and Japan. In addition, a major accomplishment toward harmonizing rules internationally took place in February, when the CFTC and European regulators reached an agreement that ensures European and U.S. clearinghouses can continue to provide clearing services to firms in each other’s jurisdiction. The agreement ensures European market participants can carry on clearing derivatives trades on U.S. clearinghouses without incurring higher capital charges. That allows U.S. clearinghouses to remain competitive, and ensures that the global derivatives market can continue to efficiently serve the many businesses that use it. This agreement brought the U.S. and European regimes closer together and reduced the risk of regulatory arbitrage. It also makes sure clearinghouses on both sides of the Atlantic are held to high standards, which will enhance global financial stability and resilience. The Commission is already working to continue this progress, such as in the area of trading requirements, for example. Specifically, CFTC staff is working with their European colleagues on the process of recognizing of each other’s trading platforms.

The Commission has taken additional steps to promote international cooperation and harmonization. It has approved the registration of six clearinghouses located outside the United States, and staff has issued exemptive orders to several foreign clearinghouses, which allow them to clear proprietary swap trades for their U.S. members and the members’ affiliates without having to register with the CFTC. This includes orders for clearinghouses in Australia, Hong Kong, Japan, Korea, and temporary relief to others, such as in China. In addition, the Commission has formalized a process so foreign exchanges seeking to provide direct electronic access to U.S. citizens officially register as a foreign board of trade (FBOT). The CFTC has approved the registration of 14 exchanges as FBOTs and is currently reviewing additional applications.

The Commission will continue to be actively engaged with international regulators in IOSCO, where the CFTC is a member of the IOSCO Board and serves in leadership positions on various IOSCO committees. In addition, the Commission will continue its work with the Financial Stability Board, where it participates in several working groups. Similarly, Commission staff will continue to participate in, other international bodies and groups in order to develop international standards for DCOs, trading platforms, and various market activities. The Commission will continue to develop and maintain strong bilateral relationships with major foreign regulators, especially in emerging markets like China and India and developed markets like Europe, Japan, Singapore and Hong Kong.

Responding to the Needs of Commercial End-Users

In all the work of the Commission, staff is mindful of acting in the interest of commercial end-users, to ensure they can continue to use the derivatives markets efficiently and effectively. These commercial businesses have traditionally relied on these markets to hedge routine commercial risk, and they did not cause the global financial crisis.

Therefore, all the Commission’s work is carried out with a focus on ensuring that its rules do not create undue burdens on these businesses, and we have taken several actions over the past year to this effect.

For example, the Commission finalized amendments to its rules on trade options that recognize these are different from the swaps that are the focus of the Dodd-Frank reforms. These changes will reduce the burdens on the commercial businesses that rely on them—and allow these companies to better address commercial risk. The Commission also reduced certain recordkeeping obligations related to end-users’ commodity interest and related cash or forward transactions.

In addition, as part of the Commission’s work to finalize its position limits rule, it unanimously proposed a supplemental rule that would ensure that commercial end-users can continue to engage in bona fide hedging efficiently for risk management and price discovery. It would permit the exchanges to recognize certain positions as bona fide hedges, subject to CFTC oversight.

This proposal is a critical piece of our effort to complete the position limits rule in the near future, as was the Commission’s 2015 proposal to streamline the process for waiving aggregation requirements when one entity does not control another’s trading, even if they are under common ownership. The Commission is also working to review exchange estimates of deliverable supply so that spot month limits may be set based on current data.

The Commission will continue to make being responsive to the concerns of end-users a priority in the years to come.

5 The sanctions ordered represent civil monetary penalties, disgorgement, and restitution. (back to text)

-

Forward Looking – Future Business Trends and Events – Part 1

There are some core principles that motivate the Commission’s work in implementing the Dodd-Frank Act. The first is that the CFTC must never forget the cost of the financial crisis to American families, and it must do all it can to address the causes of that crisis in a responsible way. The second is that the United States has the best financial markets in the world. They are the strongest, most dynamic, most innovative, most competitive and transparent. They have been a significant engine of U.S. economic growth and prosperity. The Commission’s work should strengthen U.S. markets and enhance those qualities in a way that does not place unnecessary burdens on the dynamic and innovative capacity of the industry.

It has now been eight years since the global financial crisis, and the Commission has taken a number of steps to improve the safety and soundness of our financial system. However, the work of the Commission does not just involve looking to the causes of past crises. An equally important part of the CFTC’s work is looking ahead, to the new opportunities and challenges facing these markets.

The financial markets are evolving and innovating at the speed of light. Transformations in technology are playing a large role in those changes, and from them come new opportunities as well as challenges. In turn, market participants are altering their activities—and strategies—in response. As the industry continues to evolve, the CFTC must also take steps—to ensure our regulatory framework is able to respond to the challenges ahead.

This understanding is critical to the Commission’s ability to appropriately regulate the industry of today and tomorrow. What follows is a brief discussion of what the Commission expects in the years to come.

Instances of Cyber-Attack Warrant Increased Vigilance