Statement of Commissioner Dawn D. Stump Regarding Proposed Rule: Position Limits for Derivatives

January 30, 2020

Overview

Reasonably designed. Balanced in approach. And workable in practice – both for market participants and for the Commission. These are the 3 guideposts by which I have evaluated the proposal before us to update the Commission’s rules regarding position limits for derivatives. Is it reasonable in its design? Is it balanced in its approach? And is it workable in practice for both market participants and the Commission? Overall, I believe the answer to each of these questions is yes, and I therefore support the publication of this proposal for public comment.

There is one question that I have not asked: Is it perfect? It is not. There are two particular areas discussed below that I believe can be improved – the list of enumerated hedging transactions and positions, and the process for reviewing hedging practices outside of that list.

But in reality, how could a position limits proposal ever achieve perfection? In Section 4a(a) of the Commodity Exchange Act (“CEA”),[i] Congress has given the Commission the herculean task of adopting position limits that:

- It finds necessary to diminish, eliminate, or prevent an undue and unnecessary burden on interstate commerce as a result of excessive speculation in derivatives;

- Deter and prevent market manipulation, squeezes, and corners;

- Ensure sufficient market liquidity for bona fide hedgers;[ii]

- Ensure that the price discovery function of the underlying market is not disrupted;

- Do not cause price discovery to shift to trading on foreign boards of trade; and

- Include economically equivalent swaps.

And it must do so, according to the CEA’s purposes set out in Section 3(b), through a system of effective self-regulation of trading facilities.[iii]

These statutory objectives are not only numerous, but in many instances they are in tension with one another. As a result, it is not surprising that each of us will have a different view of the perfect position limits framework. Perfection simply cannot be the standard by which this proposal is judged.

But after nearly a decade of false starts, I believe the proposal before us brings us close to the end of that long journey. It is reasonably designed. It is balanced in its approach. And it is workable in practice. I am pleased to support putting it before the public for comment.

The Commission has a Mandate to Impose Position Limits it Finds are Necessary

Background

Before digging into the substantive provisions of the proposal, let me offer my view on a legal issue that has been debated seemingly without end throughout the past decade in the Commission’s rulemaking proceedings and in federal court. As noted in testimony by the CFTC’s General Counsel in July 2009, a year before the Dodd-Frank Act[iv] became law, the CEA has always given the Commission a mandate to impose federal position limits – that is, a mandate to impose federal position limits that it finds are necessary.[v] The issue that has consumed the agency, the industry, and the bar is this: Did the amendments to the CEA’s position limits provisions that were enacted as part of the Dodd-Frank Act strip the Commission of its discretion not to impose limits if it does not find them to be necessary?

I consider it unfortunate that the Commission has spent so much time, energy, and resources on this debate. That time, energy, and resources would have been much better spent focusing on the development of a position limits framework that is reasonably designed, balanced in approach, and workable in practice for both market participants and the Commission – which simply cannot be said of the Commission’s prior efforts in this area. But, in the words of American writer Isaac Marion in his “zombie romance” novel Warm Bodies: “We are where we are, however we got here.”[vi] And so, a few thoughts on necessity and mandates.

In the ISDA v. CFTC case, a federal district court in 2012 vacated the Commission’s first post-Dodd-Frank Act attempt to adopt a position limits rulemaking. The court concluded that the Dodd-Frank Act amendments to the position limits provisions of the CEA “are ambiguous and lend themselves to more than one plausible interpretation.” Accordingly, it remanded the position limits rulemaking to the Commission to “bring its experience and expertise to bear in light of competing interests at stake” in order to “fill in the gaps and resolve the ambiguities.”[vii]

The Commission attempted to follow the court’s directive in a proposed position limits rulemaking published in 2013. There, the Commission concluded that the Dodd-Frank Act required the agency to adopt position limits even in the absence of finding them necessary but, “in an abundance of caution,” also made a finding of necessity with respect to the position limits that it was proposing.[viii] The Commission promulgated this same analysis when, three years later, it re-proposed its position limits rulemaking in 2016.[ix] The proposal before us today, by contrast, bases its proposed limits solely on finding them to be necessary – albeit a finding of necessity that is different from the one relied upon in the 2013 Proposal and the 2016 Re-Proposal.

Practical Considerations

I find the analysis put forward by our General Counsel’s Office in the proposed rulemaking before us today – which explains the Commission’s legal interpretation that its mandate to impose position limits under the CEA exists only when it finds the limits are necessary – to be well-reasoned and compelling. I add two practical considerations in support of that conclusion.

First, if Congress in the Dodd-Frank Act had wanted to eliminate a necessity finding as a prerequisite to the imposition of position limits, it could simply have removed the requirement to find necessity that already existed in the CEA. That it did not do so indicates that on this point, the CEA both before and after the Dodd-Frank Act provides that the Commission has a mandate to impose position limits that it finds are necessary.

Second, I do not believe that Congress would have directed the Commission to spend its limited resources developing and administering position limits that are not necessary. We must be careful stewards of the taxpayer dollars entrusted to us, and absent a clear statement of Congressional intent to do so, I do not believe those dollars should be spent on position limits that the Commission does not find to be necessary to achieve the objectives of the CEA.

Statutory Analysis

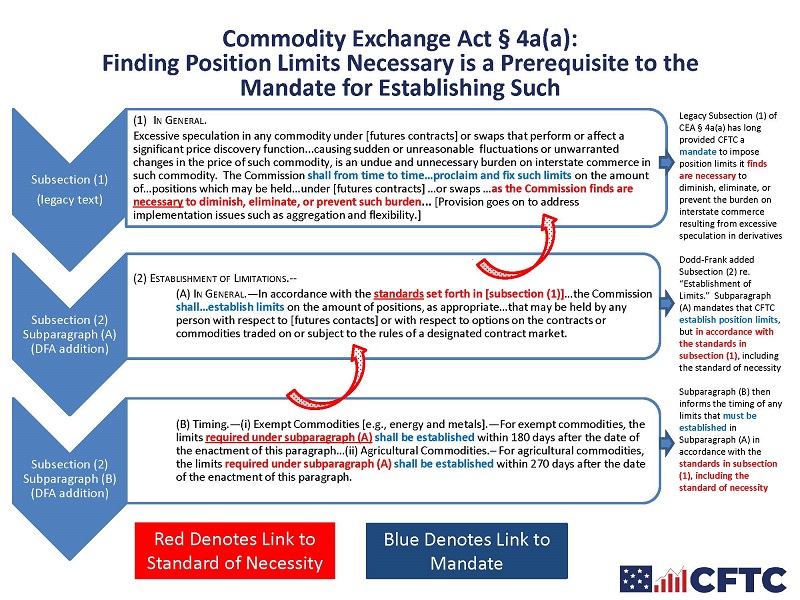

For purposes of this statutory analysis, please refer to the attached diagram entitled “Commodity Exchange Act § 4a(a): Finding Position Limits Necessary is a Prerequisite to the Mandate for Establishing Such.” This diagram walks through some of the statutory text in CEA Section 4a(a) that is relevant to the question of whether a finding of necessity is a prerequisite to the Commission’s mandate of imposing position limits.

Subsection (1) of Section 4a(a) (quoted at the top of the diagram) is legacy text that has been in the CEA for decades. As noted above, it has long mandated that the Commission impose position limits that it finds necessary to diminish, eliminate, or prevent the burden on interstate commerce resulting from excessive speculation in derivatives. Subsection (2) of Section 4a(a), on the other hand, was added to the CEA by the Dodd-Frank Act.

In my view, Subsections (1) and (2) are linked, and cannot each be considered in isolation, because the Dodd-Frank Act specifically tied them together. First, Subparagraph (A) of Subsection (2) (quoted in the middle of the diagram) links the Commission’s obligation to set position limits to the “standards” set forth in Subsection (1) – including the standard of finding necessity as a prerequisite to the mandate of imposing position limits. Then, Subparagraph (B) of Subsection (2) (quoted at the bottom of the diagram) links the timing of issuing position limits to the limits required under Subparagraph (A) – which, as noted, is connected to the standards set forth in Subsection (1), including the standard of finding necessity.

In sum, the new timing provisions in Subparagraph (2)(B) (at the bottom of the diagram) apply to the requirement in Subparagraph (2)(A) (in the middle of the diagram). Subparagraph (2)(A), in turn, informs how Congress intended the Commission to establish limits, i.e., in specific accordance with the standards in Subsection (1) (at the top of the diagram) – which includes the necessity standard. They are all linked.

Yet, some have relied in isolation on the “shall . . . establish limits” wording in Subparagraph (A) of Subsection (2) to argue that the Dodd-Frank Act imposed a mandate on the Commission to establish position limits even in the absence of a finding of necessity. Some also have pointed to the timing provisions in Subparagraph (B) of Subsection (2) to argue that the Dodd-Frank Act imposed a mandate on the Commission to establish position limits because Subparagraph (B) twice says that position limits “shall be established.” I agree that, under Subparagraph (B), position limits “shall be established” as required under Subparagraph (A) – but as noted, Subparagraph (A) states that the Commission shall establish limits “[i]n accordance with the standards set forth in [subsection (1)].” This latter point cannot be overlooked or ignored.

Some also have asked why Congress would add all this new language to CEA Section 4a(a) if not to impose a new mandate. Yet, it makes perfect sense to me that while expanding the Commission’s authority to regulate swaps in the Dodd-Frank Act, Congress took the opportunity to review and enhance the Commission’s position limit authorities to ensure they were fit for purpose considering the addition of the new expanded authorities, including how swaps would be considered in the context of position limits. The timing of the review period was spelled out and the manner in which the Commission would go about establishing limits was refined to account for this massive change in oversight.

But never did anyone suggest that the legacy language in Subsection (1) of Section 4a(a), including the required prerequisite of a necessity finding, had effectively been eliminated and replaced with a new mandate that would apply even in the absence of a necessity finding.

Subsequent History

Finally, as noted above, the court in ISDA v. CFTC instructed the Commission to use its “experience and expertise” to resolve the ambiguity it found in the statute. That experience and expertise cannot look only to the era in which these position limit provisions were enacted. We are where we are, and so the application of the Commission’s experience and expertise must include a consideration of the substantial changes in the markets since that time.

Given the intervention of a global financial crisis, it is hard to recall that the Dodd-Frank Act amendments to the CEA’s position limit provisions were borne at a time of skyrocketing energy prices during 2007-2008. The price of oil climbed to over $147 a barrel in July 2008, which represented a 50% increase in one year and a seven-fold increase since 2002.[x] Gas prices at the pump peaked at over $4 a gallon in June and July of 2008.[xi]

Some at the time charged that these price spikes were caused by excessive speculation in futures contracts on energy commodities traded on U.S. futures exchanges – another topic of debate on which I will save my views for another day. But not surprisingly, legislation soon followed. By the end of 2008, the House of Representatives had passed amendments to the CEA’s position limit provisions,[xii] and after the Senate failed to act, the issue was subsequently addressed in the Dodd-Frank Act.

How times have changed. The United States, due to a boom in oil and natural gas production relating to shale drilling and the development of liquefied natural gas, will soon become a net energy exporter.[xiii] Although no new federal position limits have been imposed, prices of energy commodities have generally dropped and stabilized, and cries of excessive speculation in the derivatives markets are rare. Also, our derivatives markets have grown substantially. Global trading in listed futures and options increased from 22.4 billion contracts in 2010 to a record 34.47 billion contracts in 2019. Global open interest increased to a record 900 million contracts from 718.5 million in 2010.[xiv]

Applying our experience and expertise, what these developments teach us is that economic conditions change over time. Technology marches on. Markets evolve. And prices fluctuate in response to a myriad of influences. Having lived through the energy price increases of the mid-2000s, I do not minimize the pain they caused, or the importance of the Commission taking appropriate steps to prevent excessive speculation in derivatives markets that can contribute to a burden on interstate commerce. Given the history of the past decade, however, I do not believe Congress intended, based on the moment in time of 2007-2008, to forever lock our derivatives markets into a straightjacket, or to deny the Commission the flexibility to draw conclusions of necessity based on particular circumstances.

Returning to our zombie romance, I’m afraid I have not been fair to its author. That is because there is a second line to the quotation, which reads: “We are where we are, however we got here. What matters is where we go next.”[xv]

It is my fervent hope that the majority of comment letters we receive on today’s proposal provide constructive input on where the proposal would take us next with respect to position limits – and not simply fan the flames of the necessity debate. And it is the topic of where we go next that I will now turn.

What Position Limits Are Necessary?

Having concluded that the CEA mandates the Commission to impose position limits that it finds are necessary, the question then becomes: What position limits are necessary?

In the 2013 Proposal, the Commission’s necessity finding determined that federal spot month position limits were necessary for 28 core referenced futures contracts on various agricultural, energy, and metals commodities. In the 2016 Re-Proposal, the Commission utilized the same necessity finding to determine that federal spot month limits were necessary for 25 of the 28 core referenced futures contracts for which they had been found necessary in 2013.[xvi] And today’s proposal, although utilizing a different approach to the necessity finding, determines that federal spot month limits are necessary for the same 25 core referenced futures contracts for which they were found to be necessary in the 2016 Re-Proposal.

In other words, three different iterations of the Commission have found federal spot month position limits to be necessary for these 25 core referenced futures contracts. That degree of consistency alone demonstrates the reasonableness of this determination.

To be sure, both the 2013 Proposal and the 2016 Re-Proposal found federal position limits for non-spot months to be necessary for these 25 contracts, whereas today’s proposal does so for only the nine legacy agricultural contracts that are currently subject to federal non-spot month limits. Yet, the necessity findings in the 2013 Proposal and the 2016 Re-Proposal were based largely, if not entirely, on just two episodes: 1) the activity of the Hunt Brothers in the silver market in 1979-1980; and 2) the activity of the Amaranth hedge fund in the natural gas market in the mid-2000s.

The Hunt Brothers silver episode and Amaranth natural gas episode occurred over 30 and over 15 years ago, respectively. It also should be noted that the Commission settled enforcement actions against both the Hunt Brothers and Amaranth charging that they had engaged in manipulation and/or attempted manipulation.[xvii] Since that time, Congress has provided the Commission with enhanced anti-manipulation enforcement authority as part of the Dodd-Frank Act, which the Commission has used aggressively and serves as an effective tool to deter and combat potential manipulation involving trading in non-spot months.

Again, I do not minimize the seriousness of the Hunt Brothers and Amaranth episodes, both of which had significant ramifications. But I am comfortable with the proposal’s determination that two dated episodes of manipulation during the past 30 years do not establish that it is necessary to take the drastic step of restricting trading (and liquidity) in non-spot months by imposing position limits for the core referenced futures contracts in these two commodities – let alone for the other 14 contracts at issue. I therefore support publishing the necessity finding in the proposal before us – including the limitation on proposed non-spot month limits to the nine legacy agricultural contracts – for public comment.

Setting Limit Levels

With respect to setting position limit levels, the Commission’s historical practice has been to set federal spot month levels at or below 25 percent of deliverable supply based on estimates provided by the exchanges and verified by the Commission. Yet, some of the deliverable supply estimates underlying the existing federal spot month limits on the nine legacy agricultural futures contracts have remained the same for decades, notwithstanding the revolutionary changes in U.S. futures markets and the explosive growth in trading volume over the years. These outdated delivery supply estimates require updating.

The proposal adheres to the Commission’s historical approach, which is reasonable given the Commission’s years of experience administering federal spot month limits on the legacy agricultural contracts. And it provides a long-overdue update to deliverable supply estimates for those legacy contracts to reflect the realities of today’s markets. The proposed spot month limits for the 25 core referenced futures contracts are based on deliverable supply estimates of the exchanges that know their markets best, but that have been carefully analyzed by Commission staff to assure that they strike an appropriate balance between protecting market integrity and restricting liquidity for bona fide hedgers.

For limit levels outside the spot month, the Commission historically has used a formula based on 10% of open interest for the first 25,000 contracts, with a marginal increase of 2.5% of open interest thereafter. Again, the proposal reasonably adheres to this general formula with which the Commission is familiar in proposing non-spot month limits for the nine legacy agricultural contracts, but it would apply the 2.5% calculation to open interest above 50,000 contracts rather than the current level of 25,000 contracts.

Open interest has roughly doubled since federal limits were set for these markets, which has made the current non-spot month limits significantly more restrictive as the years have gone by. Nevertheless, I appreciate that such a change to established limits may raise concern. I am therefore pleased that the proposal includes a question asking whether the proposed increases in federal non-spot month limits should be implemented incrementally over a period of time, rather than immediately at the effective date. (There is additionally a question seeking input on the impact of increases in non-spot month limits for convergence that is of great interest to me.)

Finally, it is important to remember that the 16 core referenced futures contracts for which federal non-spot month limits are not being proposed remain subject to exchange-set position limit levels or position accountability levels.[xviii] The Commission has decades of experience overseeing accountability levels implemented by exchanges, including for all 16 contracts that would not be subject to federal limits outside the spot month under this proposal. Position accountability enables the exchange to obtain information about a potentially problematic position while it is at a relatively low level, and to require a trader to halt increasing that position or to reduce the position if the exchange considers it warranted. Exchange position accountability rules, in combination with market surveillance by both the exchanges and the Commission and the Commission’s enhanced anti-manipulation authority granted by the Dodd-Frank Act, provide a robust means of detecting and deterring problems in the outer months of a contract. The proposal reasonably continues to rely on these tools in the non-legacy contracts.

Undoubtedly, there will be those who believe the proposed spot and non-spot month limits are too high, and others who consider them too low. I look forward to receiving public comments along these lines, but expect that any such comments will include market data and analysis for the Commission to consider in developing final rules.

Bona Fide Hedging Transactions and Positions

The CEA provides that the Commission’s position limit rules shall not apply to bona fide hedging transactions or positions. It gives the Commission the authority to define “bona fide hedging transactions and positions” with the purpose of “permit[ting] producers, purchasers, sellers, middlemen, and users of a commodity or a product derived therefrom to hedge their legitimate anticipated business needs . . .”[xix] This serves as a statutory reminder of the fundamental point that the Commission is imposing speculative position limits, and since bona fide hedging is outside the scope of speculative activity, it is by definition outside the scope of the position limit rules.

The Commission’s current definition of the term “bona fide hedging transactions and positions” is set out in what is referred to as “Rule 1.3(z).” In addition to providing a definition, Rule 1.3(z) also identifies certain specific “enumerated” hedging practices that the Commission recognizes as falling within the scope of that definition and therefore not subject to position limits. Other “non-enumerated” hedging practices can still be recognized as bona fide hedging, but only after a Commission review process.

I am delighted that the proposal before us recognizes an expanded list of enumerated bona fide hedging practices than are currently recognized in Rule 1.3(z). This is entirely appropriate. Hedging practices at companies that produce, process, trade, and use agricultural, energy, and metals commodities are far more sophisticated, complex, and global than when the Commission last considered Rule 1.3(z). This is yet one more instance where the Commission’s position limit rules simply have not kept pace with developments in, and the realities of, the marketplace. In addition, the proposal would expand federal limits to contracts in commodities not previously subject to federal limits, and thus common hedging practices in the markets for those commodities must be considered for inclusion in the list of enumerated bona fide hedges.

I am particularly pleased that, at my request, the proposal recognizes anticipatory merchandising as an enumerated bona fide hedge. After all, the CEA itself identifies anticipatory merchandising as bona fide hedging activity,[xx] and the Commission has previously granted non-enumerated hedge recognitions for anticipatory merchandising. There is no policy basis for distinguishing merchandising or anticipated merchandising from other activities in the physical supply chain. Although there must be appropriate safeguards against abuse, where merchandisers anticipate taking price risk, they should have the same opportunity as others in the physical supply chain to manage their risk through recognized risk-reducing transactions that qualify as bona fide hedging.

Although the proposal refers to enumerated bona fide hedges as “self-effectuating” for purposes of federal limits, this is a bit of a misnomer. Even if a hedge is enumerated, the trader still must receive approval from the relevant exchange to exceed the exchange-set limits.[xxi] This, too, is entirely appropriate. The exchanges know their markets, and they are very familiar with current hedging practices in agricultural, energy, and metals commodities, and thus are well-suited to apply the enumerated bona fide hedges in real-time. And, as noted above, Congress has declared it a purpose of the CEA to serve the public interest with respect to derivatives trading “through a system of effective self-regulation of trading facilities . . .”[xxii]

I find perplexing what the proposal refers to as a “streamlined” process for recognizing non-enumerated bona fide hedging practices with respect to federal position limits. Pursuant to proposed 150.9, if an exchange recognizes a non-enumerated practice as a bona fide hedge for purposes of the exchange’s position limits, that recognition would apply to the federal limits as well, unless the Commission notifies the exchange and market participant otherwise. The Commission would have 10 business days for an initial application, or 2 business days in the case of a sudden or unforeseen increase in the applicant’s bona fide hedging needs, to approve or reject the exchange’s bona fide hedging recognition.

I do not believe this “10/2-Day Rule” is workable in practice for either market participants or the Commission because it is both too long and too short. It is too long to be workable for market participants that may need to take a hedging position quickly, and it is too short for the Commission to meaningfully review the relevant circumstances and make a reasoned determination related to the exchange’s recognition of the hedge as bona fide.

My preference would have been to propose that recognition of non-enumerated hedges be the responsibility of the exchanges that, again, are most familiar both with their own markets and with the hedging practices of participants in those markets. The Commission would monitor this process through our routine, ongoing review of the exchanges. I welcome public comment on the proposal’s legal discussion of the sub-delegation of agency decision making authority as relevant to this question, and on how the proposed 10/2-Day Rule might be improved in a final rulemaking to make the process workable for market participants and the Commission alike.

A Word about Economically Equivalent Swaps

CEA Section 4a(a)(5) provides that “[n]otwithstanding any other provision” in Section 4a, the Commission’s position limit rules shall establish limits, “as appropriate,” with respect to economically equivalent swaps, and that such limits must be “develop[ed] concurrently” and “establish[ed] simultaneously” with the limits imposed on futures contracts and options on futures contracts.[xxiii] I share the view that Section 4a(a)(5) thereby requires that this rulemaking encompass economically equivalent swaps, although I invite public comment from those who believe another interpretation may be permissible and appropriate.

The proposal sets forth a narrow definition of the term “economically equivalent swap,” which I believe is appropriate. A measured approach is reasonable given that: 1) the Commission’s regulatory regime for swaps remains in its relative infancy; 2) swaps have never been subject to position limits, be it federal or exchange-set limits; and 3) the implications of imposing position limits on economically equivalent swaps cannot be predicted with any degree of confidence at this time. Further, a measured approach is more workable because it is the Commission, rather than an exchange, that will be responsible for administering the new position limits regime for swaps given that: 1) many swaps trade over-the-counter (“OTC”) so there is no exchange to fulfill this responsibility; and 2) for swaps traded on swap execution facilities (“SEFs”), those SEFs lack the information about a trader’s swap positions on other SEFs and OTC that would be necessary to fulfill this responsibility.

That said, the proposed definition of an “economically equivalent swap” is broader than that used in the European position limits regime. In Europe, economic equivalence requires identical terms; the proposal, by contrast, requires only that material terms be identical. I look forward to receiving comment on this distinction, and the experience that market participants have had with the European application of position limits to swaps.

Conclusion

The fact that the Commission has been trying to update these rules for nearly a decade demonstrates the challenge presented by position limits. I am extremely grateful to the many members of our staff in the Division of Market Oversight, the Office of General Counsel, and the Chief Economist’s Office who have dedicated a significant portion of their lives to helping us try to meet that challenge. I also appreciate the efforts of my fellow Commissioners as well.

Each of us has committed that we would work to finish a position limits rulemaking. The time has come. Overall, today’s proposal is reasonable in design, balanced in approach, and workable for both market participants and the Commission. I therefore support it.

I ask market participants to view the proposal in that spirit. Please provide us with your constructive input on how we can make a good proposal even better.

[i] CEA Section 4a(a), 7 U.S.C. § 6a(a).

[ii] Section 4a(c) of the CEA further requires that the Commission’s position limit rules “permit producers, purchasers, sellers, middlemen, and users of a commodity or a product derived therefrom to hedge their legitimate anticipated business needs . . .” CEA Section 4a(c), 7 U.S.C. § 6a(c).

[iii] CEA Section 3(b), 7 U.S.C. § 5(b).

[iv] See Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act, Public Law 111-203, 124 Stat. 1376 (2010) (“Dodd-Frank Act”).

[v] “Position Limits and the Hedge Exemption, Brief Legislative History,” Testimony of General Counsel Dan M. Berkovitz, Commodity Futures Trading Commission, before Hearing on Speculative Position Limits in Energy Futures Markets at 1 (July 28, 2009) (“Today, I will provide a brief legislative history of the mandate in the CEA concerning position limits and the exemption from those limits for bona fide hedging transactions. . . . Since its enactment in 1936, the Commodity Exchange Act (CEA) . . . has directed the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) to establish such limits on trading ‘as the Commission finds are necessary to diminish, eliminate, or prevent such burden [on interstate commerce].’ The basic statutory mandate in Section 4a of the CEA to establish position limits to prevent such burdens has remained unchanged over the past seven decades) (emphasis added), available at https://www.cftc.gov/PressRoom/SpeechesTestimony/berkovitzstatement072809; see also, id. at 5 (“By the mid-1930s . . . Congress finally provided a federal regulatory authority with the mandate and authority to establish and enforce limits on speculative trading. In Section 4a of the 1936 Act (CEA), the Congress . . . . directed the Commodity Exchange Commission [the CFTC’s predecessor agency] to establish such limits on trading ‘as the commission finds is [sic] necessary to diminish, eliminate, or prevent’ such burdens . . .”) (emphasis added).

[vi] Isaac Marion, Warm Bodies and The New Hunger: A Special 5th Anniversary Edition, 97, Simon and Schuster (2016).

[vii] International Swaps and Derivatives Association v. U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission, 887 F.Supp. 2d 259, 281-282 (D.D.C. 2012) (emphasis in the original) (“ISDA v. CFTC”), citing PDK Labs. Inc. v. U.S. DEA, 362 F.3d 786, 794, 797-98 (D.C. Cir. 2004).

[viii] Position Limits for Derivatives, 78 Fed. Reg. 75680, 75685 (proposed Dec. 12, 2013) (“2013 Proposal”).

[ix] Position Limits for Derivatives, 81 Fed. Reg. 96704, 96716 (proposed Dec. 30, 2016) (“2016 Re-Proposal”).

[x] Rebeka Kebede, Oil Hits Record Above $147, Reuters Business News, July 10, 2008, available at https://www.reuters.com/article/us-markets-oil/oil-hits-record-above-147-idUST14048520080711.

[xi] Leigh Ann Caldwell, Face the Facts: A Fact Check on Gas Prices, CBS News Face the Nation, March 21, 2012, available at https://www.cbsnews.com/news/face-the-facts-a-fact-check-on-gas-prices/.

[xii] Commodity Markets Transparency and Accountability Act of 2008, H.R. 6604, 110th Cong. § 8 (2008).

[xiii] Tom DiChristopher, US to Become a Net Energy Exporter in 2020 for First Time in Nearly 70 Years, Energy Dept. Says, CNBC Business News, Energy, Jan. 24, 2019, available at https://www.cnbc.com/2019/01/24/us-becomes-a-net-energy-exporter-in-2020-energy-dept-says.html.

[xiv] Futures Industry Association, Global Futures and Options Trading Reaches Record Level in 2019, Jan. 16, 2020, available at https://fia.org/articles/global-futures-and-options-trading-reaches-record-level-2019.

[xv] See fn. 6, supra, at 97.

[xvi] The 2016 Re-Proposal did not propose that federal position limits be imposed on three cash-settled futures contracts (Class III Milk, Feeder Cattle, and Lean Hogs) that were included as core referenced futures contracts in the 2013 Proposal. See 2016 Re-Proposal, 81 Fed. Reg. at 96740 n.368.

[xvii] The 2016 Re-Proposal acknowledged that “both episodes involved manipulative intent.” 2016 Re-Proposal, 81 Fed. Reg. at 96716.

[xviii] The use of position accountability in lieu of hard limits is expressly permitted by the CEA for both designated contract markets, CEA Section 5(d)(5), 7 U.S.C. § 7(d)(5), and swap execution facilities, CEA Section 5h(f)(6), 7 U.S.C. § 7b-3(f)(6).

[xix] CEA Section 4a(c)(1), 7 U.S.C. § 6a(c)(1).

[xx] CEA Section 4a(c)(2)(A)(iii)(I), 7 U.S.C. § 6a(c)(2)(A)(iii)(I) (bona fide hedging transaction or position is a transaction or position that, among other things, “arises from the potential change in the value of . . . assets that a person owns, produces, manufactures, processes, or merchandises or anticipates owning, producing, manufacturing, processing, or merchandising . . .” (emphasis added)).

[xxi] Further, the absence of Commission approval of an enumerated bona fide hedge does not mean that the Commission has no access to data about the position or insight into the hedger’s trading activity.

[xxii] See fn. 3, supra.

[xxiii] CEA Section 4a(a)(5), 7 U.S.C. § 6a(a)(5).